When in 2014 the Islamic State committed the Camp Speicher massacre, the second largest terrorist attack in history, the terrorist group had already been trading with, and receiving money, from the French company Lafarge, which today, associated with Holcim as Lafarge-Holcim, has become the world’s largest cement company.

His workers at the Jalabiya (Aleppo) plant in Syria could not stop working despite the war, under the threat of losing their only source of income and support for their family. Exposed to jihadist groups, having to cross the ephemeral front line to go to work, they suffered threats, extortion and even exposure to crossfire. Today, we bring you an exclusive look at the testimony of victims who worked at the Lafarge factory in Jalabiya, Syria. These victims, forgotten by all, are demanding the return of the rights and dignity that the factory took away from them, putting economic profits before their lives.

"Lafarge did not care about our safety. Mi eight colleagues and I were the first workers kidnapped from the plant"

In 2016, the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), together with the NGO called “Sherpa” and 11 former Lafarge employees, denounced the company in Paris for illegal activities in Syria between 2013 and 2014.

The activities they denounced from the ECCHR were financing terrorism, complicity in war crimes, complicity in crimes against humanity, deliberately endangering people and labor exploitation in unworthy conditions of forced labor. Parallel to this denunciation, a hundred former workers of the Jalabiya plant now inside and outside Syria have organized to take legal action against the company.

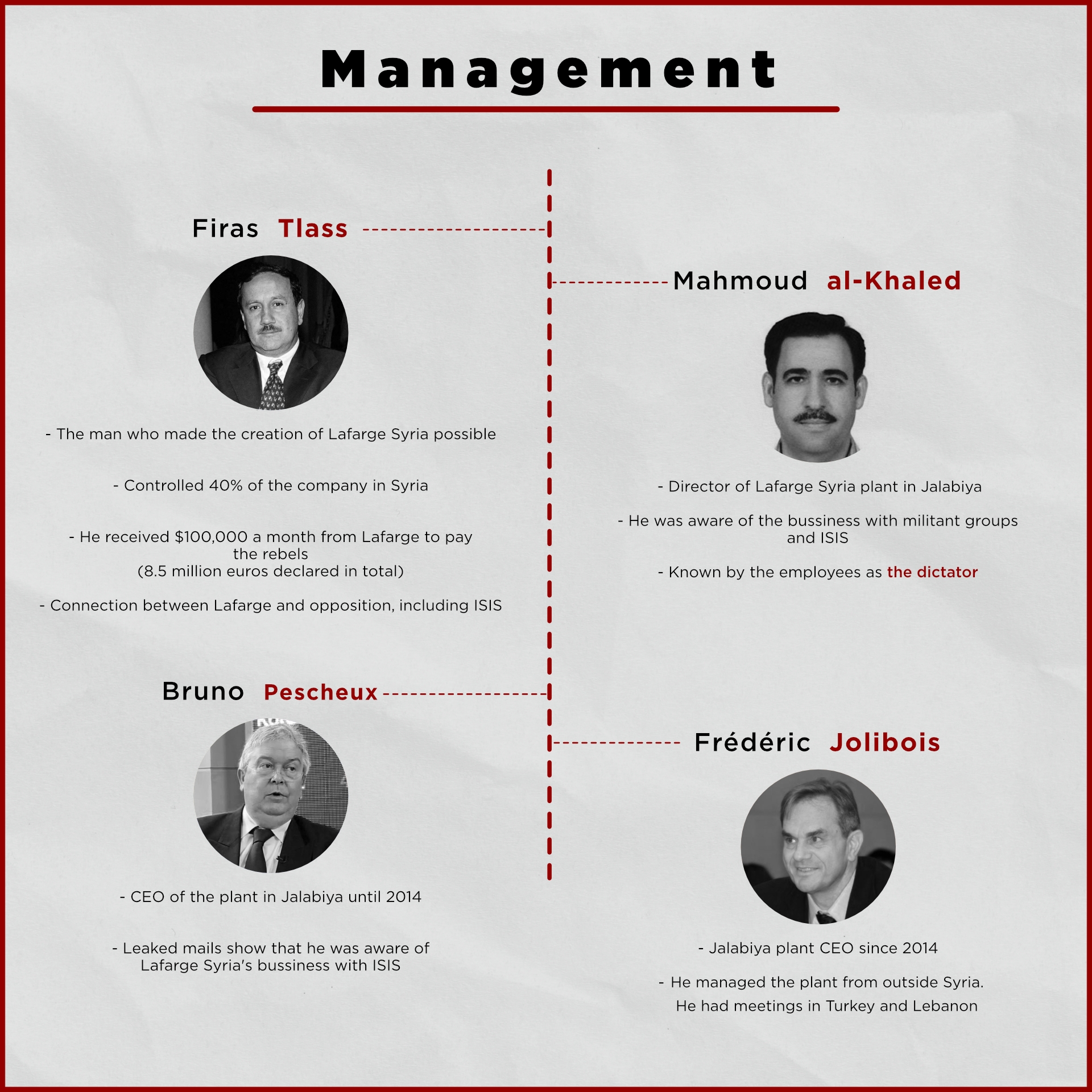

Mahmoud al-Khaled and Bruno Pescheux with the workers of Lafarge Siria

The origin of Lafarge Syria

At the end of the 2000’s, with the reforms of Bashar al-Assad’s government which, after the Cold War and inspired by the ideas of the economist Mohammad al-Imadi tended towards technocratisation and liberalisation of the state, the economy of the republic was more open to foreign investment.

In this context, the magnate Firas Tlass, son of the former Syrian Defence Minister Mustafa Tlass (1972-2004), reached an agreement with the Egyptian billionaire Nagueb Sawiris, executive president and owner of 50% of Orascom (telecommunications, construction, hotels, holding and technology) to open a cement factory in Syria.

During the construction of the new cement plant in Jalabiya, 150 kilometers from the city of Aleppo, between Manbij, Raqqa and Kobane, Lafarge began to be interested in the project, and this ambitious became a reality when they partnered with Orascom, creating from this union Lafarge Syria; where Firas Tlass became part of the board of directors.

Based in Paris and founded in 1833, in 2007 Lafarge was already going through one of its best times, with assets in 61 countries, profits of around one billion dollars, and standing out as a globally leading company in construction materials, specifically cement.

Financing of the reconstruction of the Jalabiya cement plant*

*information obtained from Wikileaks

%

European Investment Bank

%

Other institutions such as AFD y KfW

%

Private equity

Introducing Lafarge into the agreement, meant that in 2009, the European Investment Bank financed 25% of the plant’s construction. In e-mails published by Wikileaks, they add that the remaining 75% was financed by 25% other institutions and 50% capital sponsors. According to Syrian Report, the French Agency for Development (AFD) lent 40 million dollars to Lafarge Syria in a project that, according to the Financial Times, costs 680 million dollars and three years to be completed. A former employee confirms that construction of the Jalabiya plant began in mid-2007. The AFD began operations in Damascus in 2009, with an official opening in October of the same year, in a Syrian political context that the French considered «favourable». The Lafarge Syria project attracted other European investors such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the German development bank KfW. Thus, on 14 October 2010, the Jalabiya cement factory is fully operational and begins to operate.

«I started in 2010. There was no danger in Syria then, so I took the job because it paid much better than the national companies. They had an office in Damascus and a plant in Aleppo, so I had to travel with my family from Hama to Manbij and tbe surrounding areasar. After November 2011 everything started to change.

The Syrian government began to weaken in this area, and some men began to arm themselves. The company (Lafarge) never cared about that. They started financing them no matter what group; first PKK (YPG), then the Syrian Free Army and then the Islamic State,» says Samee, a former worker at the plant.

No wonder relations between Lafarge and the opposition or insurgency to the Syrian state began with the YPG. His political arm, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), has a good relationship with France, and the YPG and PYD have received direct support from the French, and their spokespersons have met at the Elysée Palace with François Hollande first, and Emmanuelle Macron later. An investigation in Khalabiya carried out in 2018 by the Complément d’enquête programme for France 2, showed that Lafarge had given $5.5 million between 2011 and 2013 to the YPGs first (the first to be established) and Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS later (from 2012).

The war begins

By the end of 2011, the protests in Syria lead to an armed conflict and all-out war by 2012. At this point Lafarge issued repatriation orders for his foreign employees, but the Syrian workers had to stay and continue to perform their duties despite having to cross checkpoints from the different sides who were taking part in the war. Lafarge threatened his Syrian employees with suspension of their wages or dismissal if they did not come to the factory. This led to some workers like Samee being kidnapped and tortured. Others, less lucky, ended up executed.

«When the war broke out, my wife and I had to go into hiding so we wouldn’t be beheaded because we belonged to a religious minority. Lafarge didn’t support me even with a word, so in August 2012 I drove my family out of town in the that we resided even though I stayed to continue working. My managers insisted that everything was fine and that nothing would happen to me,» explains Samee.

Samee explains that over time, he has discovered that they were lied to. That although his manager insisted that everything was fine, there were sectarian groups in the area such as Ansar al-Islam and Jabhat al-Nusra. When asked about Lafarge’s relationship with these groups, Samee explains that there was a direct collaboration: «when they needed cement to build their tunnels and trenches the manager would give it to them.

At present, Lafarge has admitted to having reached «unacceptable agreements» to maintain the operation of the cement plant, although it refuses to explain the extent of these agreements.

Several former employees of Lafarge Syria assure us that «it is not a question of agreements to continue operating» but of «direct collaboration and financing». Several emails leaked by the media Zaman al-Wasl in 2016 confirm that Lafarge was buying oil from ISIS.

It is important to open a parenthesis to explain that the Islamic State made oil smuggling one of its biggest sources of financing; reaching between 47,000 and 100,000 barrels of oil per day to smugglers in 2015 according to the author of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime Mahmut Cengiz.

"Lafarge did not respect its employees. I worked with heavy equipment, carrying more than 100kg on my shoulders in distances of more than 120 meters. That damaged my spine and I actually had to have surgery. Now I have a disability in my spine (...) the factory was surrounded by terrorist groups. They made us live in the factory and in Manbij, 75 kilometres away, traveling on 55 passenger buses being highly exposed to accidents. There was another danger going to the factory, and it was the terrorist checkpoints along the way. I myself was arrested in by ISIS for 24 hours in order to pressure the company to pay money. Lafarge did nothing for me, and there are many employees who were also arrested by terrorist groups. Abdul Rahman Akrab was captured by the PKK near the factory. Abdul Latif Zayata was captured by ISIS. There are others who were christians and were captured by Islamic State for much longer"

One of these emails shows a conversation between Mahmoud al-Khalid (manager of Lafarge Syria, general manager of the company and director of purchasing) and Bruno Pescheux (CEO of the Jalabiya plant) in which they talk about the «future problems» that buying oil from the Islamic state could cause; being aware at all times of what they are doing, trying to prepare a defense and justifying themselves in that they need to do so to maintain the plant and that it is a tiny amount compared to what is smuggled into Turkey.

«He made us keep working non-stop despite the risks while he was safe» sentence Khaled, former employee of Lafarge, after asking him about Mahmoud al-Khalid. «This man loves money, and he just wants to look good in front of the company; he wants to show off. He only thinks about him, about business, about power» he concludes.

Several employees think that the kidnappings were another way of financing the rebel groups by taking advantage of a legal limbo. The NGO Sherpa, which has taken the company to court, has also denounced Lafarge as an accomplice to the kidnappings of its employees.

Samee claims that his manager was lying when he told him that everything would be fine and that the employees were safe. We asked him why he thinks that.

«After 30 days off work, my manager called me to go to the plant. Also they called some of my colleagues”

My son asked me to please not go, that it was dangerous and that I would be killed, but I didn’t listen to him so my eight friends and I got on the bus to the plant. Everything was going well, so a few kilometers before we arrived I called my wife to reassure her that we had arrived.

Suddenly a group of horrible armed men, stopped the bus. They were Muslims and started shooting in the air while saying terrifying sectarian phrases because we all belonged to religious minorities. They got on the bus and as they put their guns in our faces and took us away, I don’t know where, but maybe Manbij. They put us in a small room while they kept pointing their guns at us. Some of us had the knife put to our necks while they said they were going to behead us.

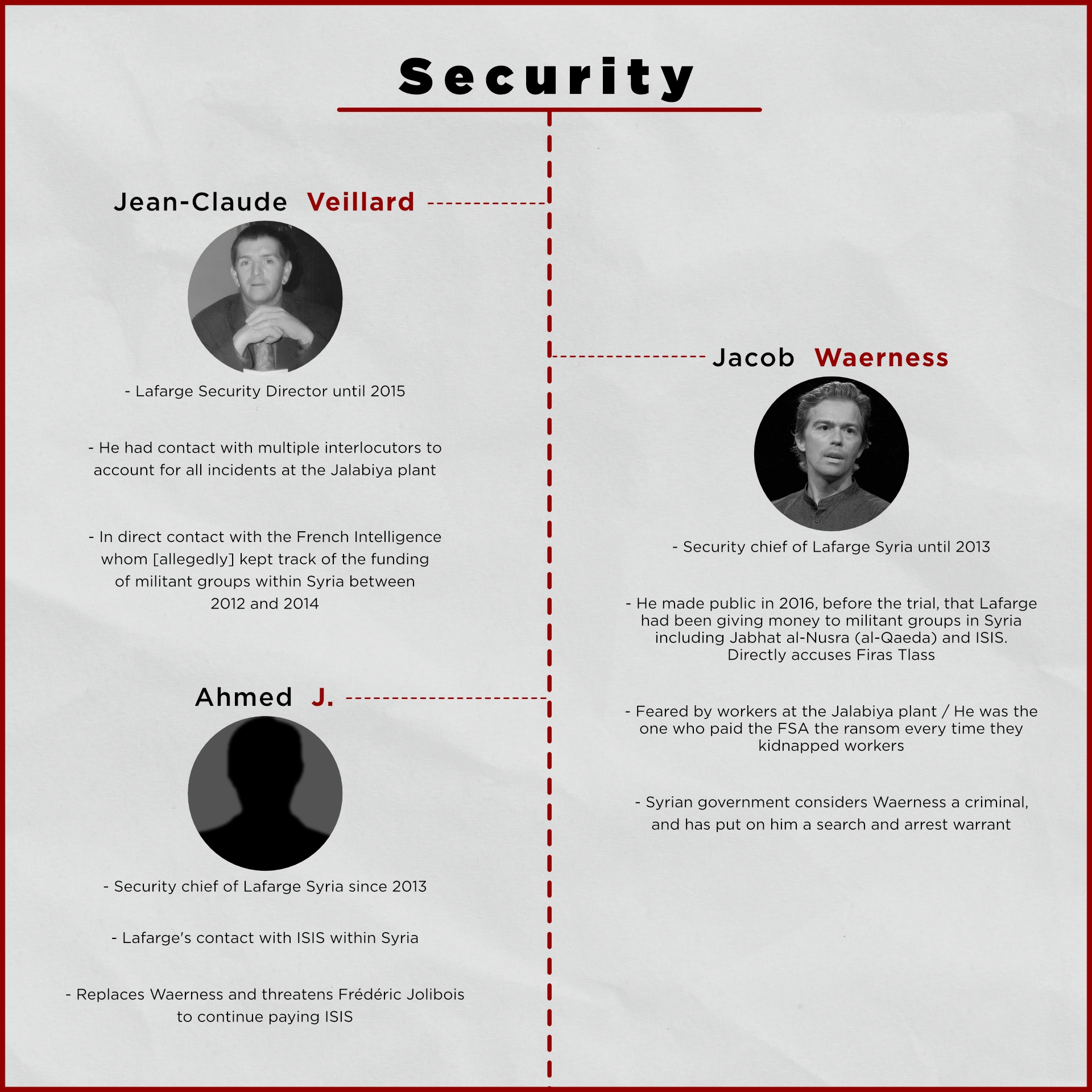

I prayed for my death to be quick. Then they stripped us. One of them burned me with a cigarette in my face. At first we were told to call the company (Lafarge), and they gave us the number of the risk manager, Jacob Waerness, but nobody answered. The people who had kidnapped us were biting and eating our skin, pulling it off, they were like monsters. I remember the bite on my back…» That’s enough, Samee can’t go on, but after a while and talking about other subjects he decides to continue:

«They used all kinds of tools to cut us. I started to hate this country because I could not get out of it. After three days of being kidnapped, they made me call my wife. They forced me to call her and tell her that they were going to cut off my head. At that time I had two children, a six-year-old and another baby. My wife was seven months pregnant and we were waiting for the third, but after the call she lost it. I can’t explain the pain. No one in command at Lafarge could bear this pain,» he concludes.

According to Samee, the release of his colleagues and him was a simple procedure for the company. He explains that the middleman showed up with two suitcases full of dollars (about 200,000) and that the company never cared about them again except to force them to continue working or leave their position. The third alternative left was to sue them in the Syrian court, but the employees knew that facing such a strong company in the Syrian context was not going to work out.

«I was kidnapped for 21 days, mostly blindfolded. We were often moved around, but we were always in the same place together. After the 21 days, without warning, they tied us up in the early morning and took us to a tower near the cement plant. They called us by name and put us in a big car. When our kidnappers received our bags, they took us to the plant. In the morning Jacob handed us over to the Syrian Army and the miracle happened. We were finally safe» finishes Samee When asked about risk manager Jacob Warness, a former Norwegian army officer, Samee says he returned to the factory because he knew he was safe. The workers who were kidnapped never received compensation. Samee’s family was left without an income but with post-traumatic stress and the feeling that no one cares about them3.

Another former employee, Khaled, claims that kidnappings were not exclusive to ISIS and were practiced by all rebel groups present in the area. «There were many armed groups in the area with many names. They were the so-called rebels. I remember the kidnappings, and at first they were not ISIS,» says Khaled.

"I suffered agoraphobia, and had no money, no hope and lost my baby. Lafarge destroyed my life and my family. My rights must be returned to me. My colleagues and I will not give up. Until now I am jobless because no company wants to hire me due to having worked for Lafarge. I ask everyone to support us, for justice."

Firas Tlass: the first connection between the rebels and Lafarge

«He controlled 40% of Lafarge Syria; he was the godfather of the project and could have done anything. I saw him about five times at the plant. He had the power» says Samee when asked about Firas Tlass. «Although he didn’t return to the plant since he fled Syria, he knew what was going on all along. His sister who now lives in France also had a small percentage, 4% if I remember correctly,» adds Khaled.

Syrian business tycoon Firas Tlass belongs to one of the mosportant in the country since the time of the Ottoman Empire. Being one of the men Syria and having benefited from the liberalization of part of its economy, disagreed with the more socialist wing of the Ba’ath Party (the ruling party of Syria until the reforms of 2011 and 2012), showing sympathy for improving relations with the US.

In 2012 Firas Tlass and his father Mustafa Tlass, left an already war-torn Syria to openly support the opposition by funding rebel militias. This did not prevent but rather encouraged him to continue receiving money from Lafarge Syria. As the company’s risk manager in the Arab Republic, Jacob Waerness, explains in his book Risikosjef i Syria, Firas Tlass was receiving at least $100,000 per month from Lafarge to pay the rebel groups.

Citing an internal Lafarge report by Baker&McKenzie ,from the Libération, Firas Tlass received more than 8.5 million euros from the cement company for distribution to the rebel and terrorist groups that controlled northern Syria. At least half a million of this money went to the Islamic state between July 2012 and 2014. The NGO Sherpa raises the figure to 12,946,000 euros.

According to France 2’s programme ‘Complément d’enquête: les sombres affaires d’unt geant du ciment’, the French intelligence agency, the Directorate-General for External Security (DGSE) was aware of these transactions, having maintained regular communication with Lafarge Syria between 2011 and 2014. In the trial against Lafarge currently underway, it has already been demonstrated that two DGSI agents were attending Lafarge’s executive committee in April 2012 and that the company’s security director Jean-Claude Veillard had direct contact with ‘multiple interlocutors’ to report on all incidents related to the Jalabiya facilities.

These transactions between Lafarge and rebels continued despite the fact that groups such as the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra were already sanctioned by the European Union for being directly associated with al-Qaida.

Both Firas Tlass and his family are closely linked to the Syrian rebels. If the tycoon offered his fortune in 2012 «for the revolution», his younger brother Abdel Razzak Tlass chose to offer his military training, joining the Syrian Free Army and going on to command the Farouq Brigade. Abdel Razzak would later join the Authenticity and Development Front (Jabhat al-Asala wal-Tanmuya), which, financed by Saudi Arabia and part of the Mujahideen Army, is one of the most radical Salafist groups in the Syrian opposition. This, in a way, explains why Firas was the first link between Lafarge Syria and the rebels. According to Firas himself, 45 members of his family deserted to join the rebels directly or indirectly.

Ibrahim Muhammad lost part of his hand in August 2012, when working with machines he slipped and suffered the amputation of three fingers. Despite the lack of security measures that caused the accident, Lafarge has never compensated Ibrahim.

"In 2012 I took time off from work. After a while they called me from the company and told me that I had to go to the factory. On the way, when I was with my daughter crossing a Jabhat al-Nusra checkpoint, we were both kidnapped. They asked for $10,000 to free my daughter and it was paid. They asked for $15,000 for me, but it took my family five months being able to pay that money. I spend that time captured by them. The company never got involved. May family did everything and paid for everything. I was kicked out of Lafarge ten days after the kidnapping. They never worried about my safety."

The end of the business

Although Lafarge Syria’s plant in Jalabiya was in a rebellious area and surrounded by rebels in a war-torn country, the business never stopped, because war requires cement. Although the company justifies its activity by appealing to supposed losses and simple maintenance of the plant so as not to abandon it, documents to which 14 Millimetros have access, show that in 2012, during the hardest moments of the war, the turnover was counted in millions, taking out around 8,500 tons of cement per day.

Former employees of the plant in Syria say that Lafarge paid salaries to terrorists so that they could move the cement.

In 2014, however, the Syrian scenario changes completely and with it the reality on which Lafarge Syria must work. On June 29, 2014 Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed himself “the caliph” from the city of Mosul, defying al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zahawiri and turning the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant into the world’s terrorist group with more stable territory under their control. This led the group to greater intransigence towards Lafarge and greater demands. In addition, the men who had managed to normalize relations with the terrorist groups in northern Syria, Jacob Waerness and Bruno Pescheux, were no longer there and their replacements, Ahmed J. and Frédéric Jolibois, were both extremists and frightened.

Emails leaked by Zaman al-Wasl show that by 2014 the situation had gotten out of hand for Lafarge Syria’s high commanders.

On September 9, 2014, Ahmed J, the Islamic State’s contact with the Jalabiya plant, demanded that the new CEO, Frédéric Jolibois, pay two months in arrears to the terrorist group; the equivalent of seven and a half million Syrian pounds. In the e-mail, Ahmed J. stresses that ISIS is the strongest Islamist group on the ground, so «it is better not to mess with them». An important detail is that the bank account into which the money should be paid to the terrorist group was of a Lebanese bank. One of the former employees of the Jalabiya plant, Khaled, claims that Jolibois never entered Syria, and that all meetings were held in Lebanon and Turkey.

In another internal company email, Frédéric Jolibois is concerned about Ahmed’s ways, fearing that the ISIS intermediary is putting him in danger. The response Jolibois receives, is to relax and continue trading with the Islamic state. Ten days after the mail in which Ahmed J. threatens Jolibois, however, ISIS finally raids the cement plant and takes control of it by stealing parts, equipment, and Hydrazine that Lafarge had smuggled in from Turkey shortly before. Hydrazine is a highly toxic chemical used as a fuel for missiles and as an explosive for SVBIEDs (suicide vehicles) that the Islamic state turned into one of its most feared weapons.

On September 19, 2014, Lafarge Syria was a victim of the same monster that they had been helping to grow for three years. There are workers, however, who are convinced that it was not a simple business relationship between a company offering cement and terrorist groups that needed money and cement for their defensive positions and tunnels. «They could do anything. They had deals with ISIS. They had to have some power behind them,» sentence Samee.

"Lafarge has treated us poorly, we lacked of basic human rights. It delayed the evacuation of the factory after the ISIS attack, exposing us to enormous psychological pressure. The Islamic State detained us at a checkpoint at the Tishreen Dam, before reaching Manbij. We were vulnerable to being murdered or kidnapped (...) the company paid the wages in Syrian pounds, which value was falling day after day."

The death money

For at least three years, Lafarge Syria and its leadership were supporting armed groups opposed to the Syrian state, criminals and hard-line jihadists. Of all of them, the Islamic State stands out, which while maintaining contact with and receiving money from Lafarge, committed some of the biggest killings in the Middle East and the world.

Two simultaneous attacks in Baghdad and Kirkuk, killing more than 35 people and leaving more than 200 injured in January of 2013. Trucks loaded with explosives were used. In the same month of that year, a terrorist blew himself up at a funeral in Tuz Khurmato, killing 42 people.

On March 19, 2013, coinciding with the tenth anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, they carried out multiple attacks that left about a hundred deaths, and many more injured. Such attacks became so common that in 2013 alone they killed 450 people.

On the 24 of May of 2014, a fanatic of the Islamic state murdered four people in Brussels after raiding the Jewish museum. The shooter had been in Syria not long before.

But it is on June 12, 2014 that the Islamic state commits the second most lethal terrorist operation in history. The group attacked the camp of Camp Speicher (Tikrit) where no less than 4,000 unarmed cadets were present. Those who were not captured in the attack were abducted on their way to Baghdad.

That day the terrorists took more than 1,500 prisoners, all Shi’a. And that same day, the terrorists executed all of them. Relations between the Islamic State and Lafarge did not stop until three months later by decision of the terrorists.

«They kidnapped Yassin on his way to work at the Jalabiya plant. After a month without knowing about him, we heard news that ISIS had beheaded him.

The managers never asked about him. Lafarge never asked about him. His children did not even receive a compensation for losing their father.»

– Yassin’s companions

Case procedure

In September 2016, after Le Monde talked about documents leaked by Zaman al-Wasl connecting Lafarge directly to ISIS, the French Finance Minister filed a complaint with the Paris prosecutor to investigate Lafarge’s illegal purchase of oil in Syria. This decision follows the European Union’s imposition of sanctions on Syria on 18 January 2012 prohibiting the purchase and sale of its oil.

In November 2016, Sherpa, the ECCHR and 11 former Lafarge employees filed a criminal complaint in Paris against Cement Syria (Firas Tlass’ company), Lafarge Syria and its former CEOs for financing terrorism, crimes against humanity and violation of labor laws.

On July 9, 2017 three judges of the Court of Paris initiated the investigation although Lafarge filed a motion in October of the same year.

On 7 November 2019, the accusation that Lafarge may have financed the Islamic State and put its workers in danger was accepted, but it was denied that they had been complicit in crimes against humanity; something that had never been proven against an international company to date.

One of the lawyers in charge of defending Lafarge in court is the former advisor to Nicolas Sarkozy between 2007 and 2010; when the former French president obtained illegal funding for his campaign.

The European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights is calling on Lafarge to set up a compensation fund for all former employees of the company in Syria and their families, whether living in the country or abroad, for the moral damage they have suffered.

A hundred employees are looking to start another legal process on their own. When we ask Samee why he does this, he answers that he and his colleagues are only looking for justice. «I have never thought of giving up. My baby’s soul gives me the strength to not do it. I’ll fight to raise my dignity and to get my rights back,» he concludes.

"What I want from Lafarge is to be able to ask to the managers why they putted us in danger, why they didn't take responsibility for the workers and why they didn't even give us our money. Our lives, our dignity, was worth less than a bag of cement."

More than 100 former Lafarge Syria workers have decided to wage a legal battle against the company on their own. This 2020 the complaint has been accepted. Regardless of political views, all the workers have decided to unite in order to, they say, do justice; without giving up, until Lafarge restores their rights to them.